Sri Lanka’s serious levels of Hunger

As world leaders conclude this year’s UN General Assembly discussions on the sustainable development goals (SDGs) aimed at making the world a better place by addressing the social, economic and environmental issues that lead to deprivation of people and destruction of the planet, the Global Hunger Index calculated by IFPRI (the International Food Policy Research Institute) reminds us that even though the state of hunger in developing countries as a group has improved since 1990, the level of hunger in the world is still ‘serious’ with 805 million people continuing to go hungry.

Sri Lanka too seems to have ‘serious levels’ of hunger, even though our position on the Global Hunger Index rating has improved from 43rd, to 39th. The score is the best among the countries in South Asia for which the index is calculated (i.e. India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal) but given our lower middle-income status the fact that we have more levels of hunger than lower income countries like Mali (ranked 28th), or other countries in the same lower middle-income category such as Senegal (37th), Lesotho (29th) or Indonesia (22nd) is a matter of concern.

So what is the Global Hunger Index? It is an annual index calculated by IFPRI (the International Food Policy Research Institute) and combines three equally weighted indicators into one index. They are:

1. Undernourishment: the proportion of undernourished people as a percentage of the population (reflecting the share of the population with insufficient caloric intake);

2. Child underweight: the proportion of children under the age of five who are underweight (that is, have low weight for their age, reflecting wasting, stunted growth, or both), which is one indicator of child undernutrition; and

3. Child mortality: the mortality rate of children under the age of five (partially reflecting the fatal synergy of inadequate food intake and unhealthy environments).

The index reflects one of the main conundrums of Sri Lanka’s social development, the persistence of malnutrition among children and pregnant and lactating mothers, despite many achievements in the health sector, near universal immunization, a relatively high level of female education, no significant food shortages and countless initiatives to address malnourishment and child nutritional levels (Jayawardena, 2011)

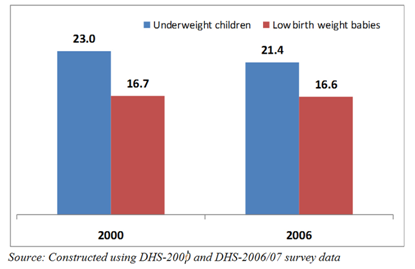

Chart 1: Underweight children and low birth weight babies, 2000 and 2006

Graph sourced from (Jayawardena, 2011)

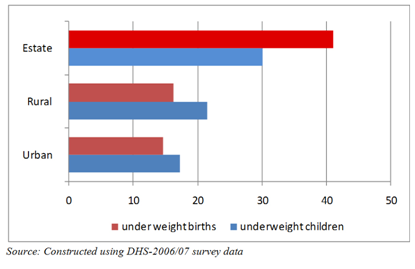

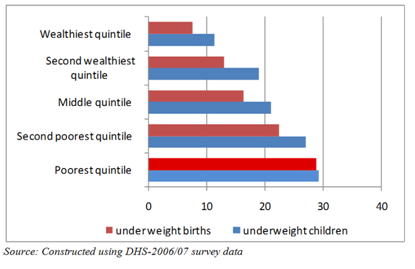

Jayewardena (2011) shows that this situation is worse for some groups – for instance children in the estate sector are particularly worse off and in the Badulla district, 1 in 3 children are underweight. Malnutrition is also related to household income, to mothers’ nutritional status, and to mothers’ level of education.

Chart 2: Underweight births and underweight children, 2006

Graph sourced from (Jayawardena, 2011)

Chart 3: Underweight births and underweight children by wealth quintiles , 2006

Graph sourced from (Jayawardena, 2011)

The Global Hunger Index calculation puts Sri Lanka’s undernourishment as 22.8% in 2012, and child underweight as 21.6% in the same year, and child mortality as 1.0%. Sri Lanka’s position in the rankings is affected by the low child mortality figures, if not for which, the Hunger Index would have been a great deal more unfavourable. The disconnect between child health (reflected in the low child mortality figure) and malnutrition is difficult to understand because the factors that lead to low child mortality (access to health services, high female literacy, good hygiene and health practices etc) should also lead to low malnutrition. It would seem that we need to look for other factors that underpin the conundrum.

UNICEF Sri Lanka suggests that while poverty in its many manifestations is an important determinant of undernutrition of children (and adults) it is not sufficient to explain the high rates of malnutrition in Sri Lanka. They propose that other determinants of malnutrition could include inappropriate feeding practices, micronutrient deficiencies and disease.

Only 76% of Sri Lankan babies are exclusively breastfed for the first six months (DCS, Demographic Health Survey). This means that several babies miss out on colustrum, and run the risk of having an over-diluted infant formula contaminated through unclean water. At the stage of complementary feeding, UNICEF observes that children are fed the wrong kind of food, often nothing much more than rice and water. At the same time the move away from traditional diets to highly processed energy dense micronutrient poor foods and drinks could also account for high undernutrition. Micronutrient deficiencies (sometimes called hidden hunger) affect healthy child growth and development. One out of every five Sri Lankan children suffer from iodine deficiency disorders, which affect their mental and physical development; one third of children less than six years old have Vitamin A deficiency which can affect their eyesight and immunity to diseases; and half the children between 5 and 10 years are deficient in iron, which leads to anaemia and impairs cognitive development. (UNICEF Sri Lanka) The statistics don’t show a very high incidence of diarhoea which could have been another determinant of malnutrition among children, but acute respiratory infections are relatively common, and are likely to contribute.

Being insufficiently high on the Global Hunger Index ranking then, is not just a problem of food security and food availability, but rather a composite of several issues that require more nuanced interventions. Sri Lanka may do well to remember this as we celebrate our middle income status and the achievement of several of the MDGs by 2015, and look towards negotiating and committing ourselves to a new set of sustainable development goals.

Reference

Jayawardena, P. (2011, November 21). Sri Lanka grapples with child malnutrition despite major improvements in the health sector.Retrieved June 4, 2012, from Talking Economics: http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/2011/11/21/sri-lanka-grapples-with-child-malnutrition-despite-major-improvements-in-the-health-sector/