A Governance Diagnostic by the Sri Lankan Public

Retired Professor Hemesiri Kotagama and Mrs Varangana Ratwatte

Researchers at Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA)

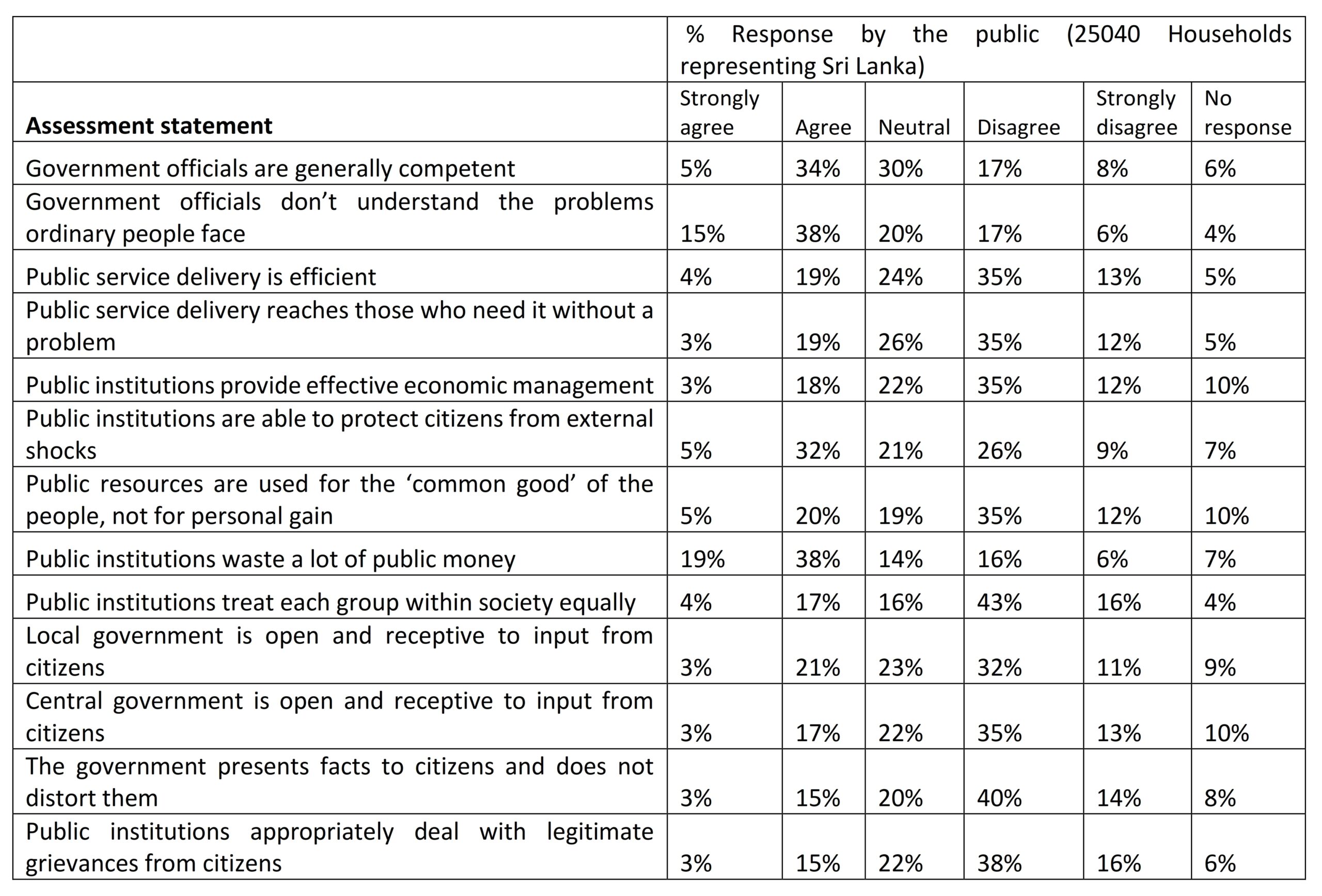

- Sri Lankan public perceives the public service as inefficient and treats different social groups unequally and inadequately addresses legitimate grievances of citizens.

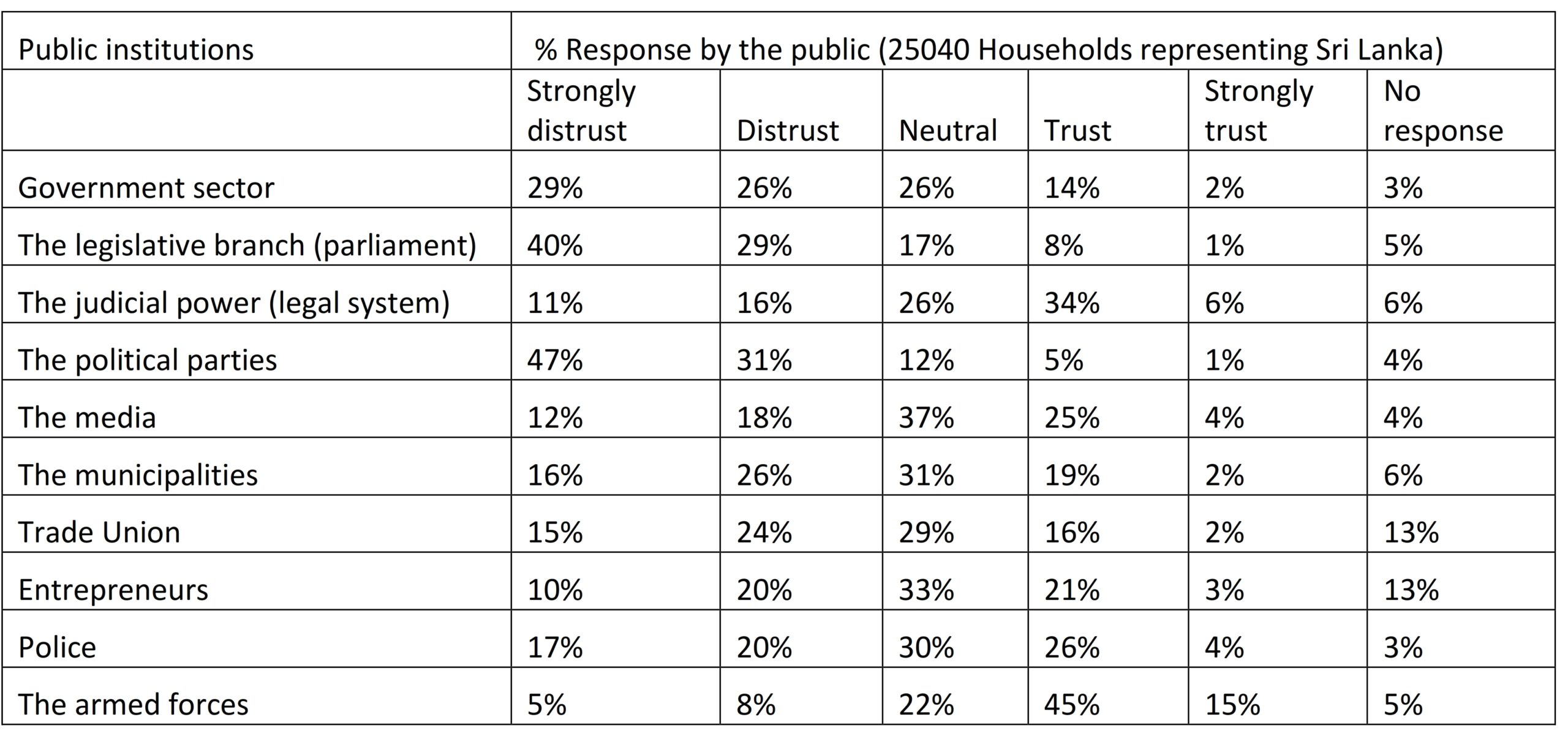

- The most trusted public institutions, by the Sri Lankan public are the legal institution, and the armed forces and the least trusted are the parliament and the political parties.

- It is opportune to consider the possibilities of a well thought and planned “System Change” on governance that was demanded by the recent social upheaval “Aragalaya”.

As the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has noted in its Governance Diagnostic Assessment (IMF, 2023, September):

“The resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa in July 2022 emphasized that addressing the crisis required changes in governance as much as changes in economic policies. The role of civil society in demanding accountability carried an equally important message about the drivers of change”.

This article is being shared in congruence with the role that the IMF has called upon civil society to play as catalysts for change in the pursuit of good governance, ultimately aiming for a harmonious and equitable Sri Lankan society. The recent IMF report on the Governance Diagnostic Assessment of Sri Lanka delivers a scathing critique of the abysmally poor performance of Sri Lankan governance. It also offers recommendations for improvement, along with a specified timeline tied to the financial assistance Sri Lanka has recently received from the IMF. The approval of the second tranche of this financial assistance is still pending review by the Governance Board of the IMF.

While the IMF’s assessment provides a macro-level view, this article offers a micro-level assessment from the perspective of the Sri Lankan public regarding the performance of the public sector and the government. The information presented is derived from an analysis of data collected by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Sri Lanka and the Department of Census and Statistics (DCS) of the Government of Sri Lanka, in collaboration with Citra Lab, other UN partners, and UNDP’s SURGE Data Hub. The data has been generously made available to the public by the UNDP (https://www.undp.org/srilanka/mvi). The sample encompasses 25,040 households representing all districts of Sri Lanka. The survey has sought public perceptions on various aspects of governance through Likert Scale responses.

According to Table 1, there is a paradoxical sentiment among the majority of Sri Lankans. They believe that government officials are competent and protective of citizens during external shocks. However, there is a prevailing perception that these officials struggle to understand the everyday challenges faced by ordinary people.

Furthermore, the Sri Lankan public perceives the public service as largely inefficient. They feel that it fails to effectively reach those in need, treats different social groups unequally, and inadequately addresses legitimate grievances of citizens.

Additionally, the public holds the view that public institutions are not managed efficiently, and that public resources are not utilized satisfactorily for the collective public good, often resulting in wastage.

Moreover, there is a widespread belief among the public that both local and central government entities are not receptive to suggestions put forth by citizens.

Table 1. Public assessment on the public sector institutions: Score card

Vide Table 2, the most trusted public institutions, by the Sri Lankan public are the legal institution/system, and the armed forces. The media and the police institutions are rather moderately trusted. Given the present circumstances of a deep economic crisis in Sri Lanka, a strong role of entrepreneurs is expected, yet the public trust on entrepreneurs is moderate. The trust on government sector, municipalities and trade unions is low. The least trusted are the parliament and the political parties.

Table 2. Public trust on public institutions: Score card

Above, scientific and objective assessment of public sector and by and large governance, is considered to be, to conclude rather mildly, is unsatisfactory. Sri Lankans do not assess public institutions as providing satisfactory services and do not trust major public institutions, such as the parliament and the political parties. It is perhaps opportune to consider the possibilities of a well thought and planned “System Change” that was demanded by the recent social upheaval “Aragalaya”.

References